Pet breeding looks like a tidy little “side business” until you’re sitting in a waiting room at 2am with a labouring queen, a panicked vet bill, and a buyer messaging you ten times about coat colour like you’re Amazon Prime. That’s the real job. And if you’re doing this in the UK, you’re not just dealing with animals, you’re dealing with licensing, inspections, records, refunds, complaints, and the occasional person who thinks “deposit” means “optional suggestion.”

The good news: most disasters are preventable. Not with vibes. With paperwork, proper systems, and a hard line on welfare.

First: are you a “hobby breeder” or a business (legally)?

This is where new breeders get cute, and that’s usually when councils get interested, buyers get suspicious, and you accidentally fall into the “running a business without realising you’re running a business” mess. You might think you’re casual because it’s from home and it’s “only a couple of litters,” but the law doesn’t care about your self-image. It cares about frequency, volume, profit motive, and welfare standards.

In England, dog breeding licensing is clear-ish: three or more litters a year often triggers licensing (plus “business” indicators even under that). Cats are murkier because national rules don’t mirror dog breeding perfectly, so local councils can be the loudest voice in the room. Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland each have their own flavour of rules too.

So. Call your local council. Ask directly what triggers licensing for cats in your area.

What councils tend to look at (even when numbers are low)

- Advertising volume (online listings, waitlists, Instagram “drops,” the lot)

- Repeat sales and deposits

- Purpose-built facilities (or a home set-up that’s effectively a mini cattery)

- How you manage hygiene, disease control, and isolation

- Recordkeeping (breeding, vet care, sales contracts)

If you’re planning to make money and scale, just accept you’re a business and build it properly. It’s less stressful than trying to hide behind “it’s just my pet having kittens.”

Licensing, welfare rules, and the boring stuff that can shut you down

UK breeders don’t get a free pass because the animals are cute. Animal welfare law sits behind everything you do, housing, enrichment, cleanliness, feeding, pain management, transport, weaning, socialisation, the whole picture. And if you end up licensed (or inspected as part of a complaint), your set-up needs to look intentional, not improvised.

Clean isn’t a weekend task. It’s an operating system.

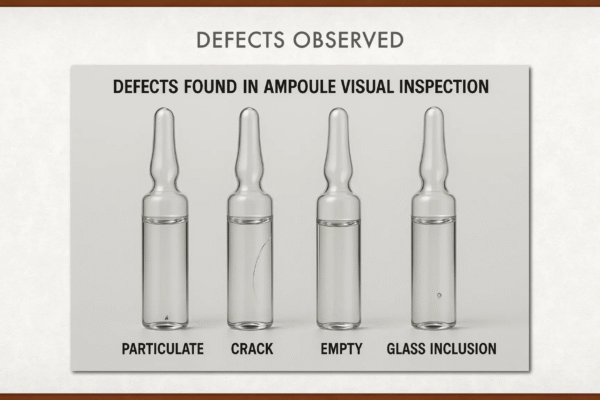

Expect scrutiny around these basics

- Space and environment: ventilation, temperature control, safe separation, noise management (neighbours can be your fastest “inspection request”).

- Biosecurity: quarantine area, visitor policy, sanitation SOPs, parasite control, and what you do if something infectious turns up.

- Vet relationship: not “I’ll find one if I need one,” but an actual plan, routine care and emergency cover.

- Waste disposal: practical, regular, and not upsetting the entire street.

This isn’t paranoia. It’s what responsible breeders do when they don’t want a disease outbreak to wipe out their animals and their reputation in the same week.

Business structure, tax, and payments: don’t wing it

Plenty of breeders start by taking deposits into a personal account, tracking costs in their head, and hoping HMRC never notices. That’s a bold strategy. It also falls apart the second you have a refund dispute, a chargeback, or a customer who wants an invoice for insurance.

Separate accounts. Day one.

Practical set-up choices (UK)

- Sole trader: simple, cheap, but you carry the risk personally.

- Limited company: more admin, but cleaner separation between you and liability (still get proper advice).

- Bookkeeping: track every vet bill, food cost, genetic test, microchip fee, and transport expense. Breeding margins are not as “easy” as people assume.

And yes, keep records like you expect to be challenged. Because you will be.

Advertising and buyer trust: your claims need receipts

“Champion bloodlines.” “Health guaranteed.” “Vet checked.” “Hypoallergenic.” Some of these phrases are normal marketing. Some of them are legal and ethical landmines if you can’t back them up, or if buyers interpret them as promises you never actually meant.

Buyers read fast. Regulators read slow.

What to say (and what to prove)

- Health testing: list exactly what’s been tested, who did it, and whether you’ll show results.

- Registrations: say which registry (GCCF, TICA, WCF, FIFe, etc.) and what that registration covers.

- Vet checks: include dates and what was examined (basic “vet checked” is vague and weak).

- Temperament: describe what you’ve actually observed, not what the breed stereotype says.

If you want a concrete example of how breeders present proof points buyers expect, testing mentions, go-home timing, health guarantees, and the whole “this is how reservations work” detail, look at pages like Maine Coon kittens in New York. Different country, sure, but the transparency pattern is the bit worth stealing.

Contracts: where most “friendly breeders” get burned

Without a proper contract, you’re basically running on handshake law and hoping everyone stays nice forever. They won’t. Someone will decide their landlord changed their mind, their child developed allergies, or their partner “didn’t realise how big Maine Coons get,” and suddenly you’re negotiating refunds like you’re in hostage talks.

Write it down. Every time.

Your sales agreement should cover (at minimum)

- Deposit terms: amount, what it secures, and when it’s refundable vs non-refundable (be clear and fair).

- Payment schedule: dates, methods, and what happens if they stall.

- Health guarantee: what’s covered, for how long, what documentation is required, and what remedy you offer (refund, replacement, contribution cap).

- Genetic issues: what tests you’ve done and what that does not guarantee (buyers love magical thinking).

- Go-home conditions: minimum age, vaccines, microchip, vet check, parasite control.

- Returns: your take-back policy (ethical breeders plan for failure cases).

- Spay/neuter requirements: if pet-only, specify timing and proof.

You’ll hear people complain that contracts “scare away good buyers.” Honestly? Good. A contract scares away flaky buyers. The good ones read it, ask a couple of smart questions, and respect you more.

Insurance: the part nobody wants to pay for (until they need it)

Insurance in breeding is confusing because normal small-business cover doesn’t always map neatly to animal-related risk, and insurers love exclusions they don’t explain until you’re already in trouble. You’re not just covering your property, you’re covering the weird edge cases: a visitor gets scratched, a buyer claims vet costs, a kitten gets sick during transport, or someone says your “healthy kitten” wasn’t healthy enough.

Bad cover is worse than none. It tricks you into relaxing.

Policies to ask about (and interrogate)

- Public liability: injuries to visitors/buyers on your premises.

- Employers’ liability: if anyone helps you (even part-time, even “cash”).

- Care, custody, and control: if you ever handle other people’s animals (stud services, boarding, guardian homes).

- Property/business interruption: fire, flood, forced closure, your animals still need care even when you can’t operate normally.

- Commercial vehicle/transport: if you deliver animals or supplies as part of the business.

- Cyber/payment risk: deposits, online invoices, customer data, small breeders get targeted too.

And ask one blunt question: “If a buyer claims the kitten had a congenital issue and wants their vet bills covered, what happens?” Watch how fast the insurer stops sounding relaxed.

Ethical breeding: not a vibe, a system

If your plan is “breed a pretty pair and hope for the best,” don’t start. Ethical breeding is structured decision-making: health screening strategy, genetic diversity, temperament selection, welfare-first housing, careful placement, and the humility to admit that not every pairing is worth doing, even if it would sell fast.

Your reputation is your only moat.

Health testing (cats): what “responsible” actually looks like

Breed-specific risks matter. Maine Coons, for example, often bring up HCM (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), SMA, and PK-def in buyer questions, and you’ll be expected to explain what you test for, what results mean, and what isn’t fully knowable. Genetic testing helps. Echocardiograms help. Neither makes you a wizard.

Testing reduces risk. It doesn’t delete it.

Breeding frequency and welfare boundaries

- Set a maximum number of litters per queen and stick to it.

- Have age limits for first litter and retirement.

- Plan how retired animals live (with you, guardian home, placement rules).

- Build enrichment into daily life, climbing, play, calm spaces, routine handling.

If you’re cutting corners because you’re busy, you’re not ready to be a breeder. You’re just producing animals.

Operational reality: biosecurity, records, and “no, you can’t visit this week”

New breeders want to be welcoming. Buyers want to see everything. And then one day you get a cough in the kitten room and you realise letting strangers wander through your space is a biosecurity hobby you can’t afford.

Visitors are risk.

Simple biosecurity rules that save you

- Quarantine new arrivals (and mean it).

- No random drop-ins. Appointments only.

- Handwashing and shoe protocols (yes, even if it feels awkward).

- Clean-to-dirty workflow (never the other way around).

- Separate equipment per room where possible.

Recordkeeping isn’t glamorous either, but it’s your shield in disputes: mating dates, weights, feeding notes, deworming schedule, vaccines, microchip numbers, vet visits, test results, buyer communications, contracts, and receipts.

If it isn’t recorded, it didn’t happen.

Buyer screening: you’re allowed to say no

A lot of “bad breeder” stories start with a breeder handing over an animal to the first person with cash, then acting shocked when it goes sideways. Screen buyers like you’re placing a living creature, not flipping a product. Because you are.

Some sales should fail.

What screening can look like (without being creepy)

- Basic lifestyle fit: work hours, other pets, kids, noise tolerance.

- Housing reality: permission from landlord, long-term plans, travel habits.

- Education: grooming needs, diet expectations, insurance, vet care budget.

- Non-negotiables: indoor-only policy, spay/neuter timing, return clause.

And have a take-back policy you can live with. If you breed it, you own the ethical responsibility for where it ends up. Lifetime support isn’t charity. It’s accountability.

A staged “do this first” checklist (so you don’t light money on fire)

- Talk to your local council: licensing triggers, inspection standards, home limits, nuisance rules.

- Vet plan: routine partner + emergency cover; ask about reproduction support.

- Define your breed standards: health tests, temperament goals, COI (inbreeding coefficient) awareness, and what you won’t compromise on.

- Insurance quotes: read exclusions, ask blunt questions, get it in writing.

- Contract drafted: deposits, guarantees, returns, spay/neuter, disclosures.

- Biosecurity SOPs: quarantine, cleaning, visitor policy, parasite control.

- Documentation pack template: vet records, microchip details, registration, feeding guide, care instructions.

Do that, and you’re already ahead of most people who “start breeding” because they saw a high price tag online and decided it looked easy.

This business can be done well. It can also be done badly, fast, profitable, and ethically grim. Pick your lane early, because once your name is associated with sloppy care or dodgy guarantees, you won’t fix it with a nicer logo.